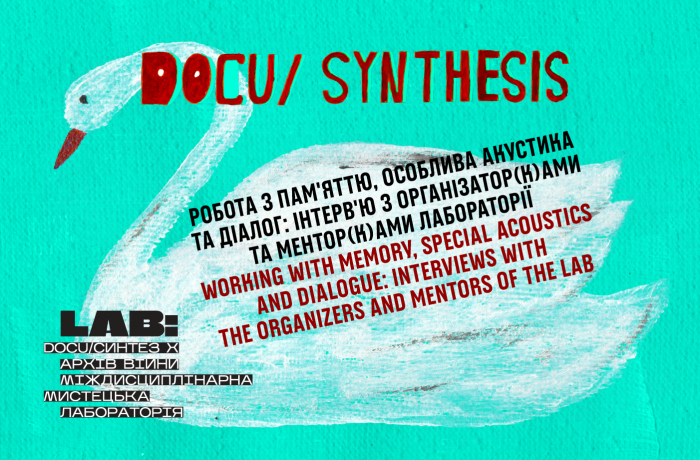

This year, the DOCU/SYNTHESIS program joined forces with the Ukraine War Archive to create an interdisciplinary art laboratory dedicated to the themes of memory and cultural heritage. Over the course of a year, LAB: DOCU/SYNTHESIS x Ukraine War Archive resulted in an exhibition of artworks, conversations with the artists, and a thematic discussion. What was this journey like? What approaches to memory and cultural heritage did the artists explore? And what is the value of working with documentary materials? We spoke with the Laboratory's mentors, curator, and the co-founder of the Ukraine War Archive to find out.

After several stages of project selection and participation in an educational module, the authors of the selected artworks received financial and mentoring support as part of the Laboratory. The final stage of this process was the exhibition How We Remember, presented within the 22nd Docudays UA. The exhibition features a range of works — including a painting, a monumental panel, installations, and films — and explores themes such as forced migration, sleep disorders, archiving, and other aspects of the overarching topic.

Manuel Correa

mentor of the LAB: DOCU/SYNTHESIS x Ukraine War Archive

How do you personally define working with memory in an artistic context?

Artistic contexts are incredibly generative spaces for engaging with memory. Often, the sites of traumatic events are either inaccessible or have been transformed beyond recognition. Through art, we can use our tools and sensibilities to reconstruct or reimagine these lost spaces, giving them new life. My practice rigorously examines the past, not for nostalgia, but as a way of forging meaningful commitments to the future.

What approaches to interpreting cultural heritage emerged within the laboratory?

The laboratory allowed me to engage with a wide range of thought-provoking projects, each with diverse and innovative approaches—ranging from sculptural installations to films and paintings. In these works, feverish dreams, distant memories, active projects, and preservation efforts were often entangled. The Ukrainian context is especially urgent today, given the ongoing war. This situation, painful as it is, also challenges us to collectively reflect on what we choose to preserve and what we let go of as a society, in order to build more just and peaceful futures.

What was your experience like working in the laboratory format?

The laboratory connected me with a number of deeply thoughtful and sensitive projects. As a mentor, I found the experience both inspiring and humbling. Over the span of several months, I had the privilege of witnessing these works take shape, grow stronger, and become more coherent.

Olha Balashova

mentor of the LAB: DOCU/SYNTHESIS x Ukraine War Archive

How do you personally define working with memory in an artistic context?

Working with memory in the realm of art is the top priority right now. We need a new language of remembrance — not only for the events of the ongoing war, but also for the broader healing and processing of historical wounds. I believe that only artists can create this new language of memory: one that is honest, empathetic, and responsible.

What approaches to interpreting cultural heritage emerged within the laboratory?

New and unexpected ways of working with heritage emerged within the Laboratory. The space for free, unrestricted, yet informed exploration created by the project team likely enabled the development of several new working formats. I’m very much looking forward to seeing the participants’ finalized projects and evaluating the results.

What was your experience like working in the laboratory format?

This experience is both inspiring and therapeutic. In truth, none of us knows the right way — and that’s why we are deeply engaged in this shared search. You could say we are learning from one another how to speak publicly about difficult and painful topics. This process requires trust, compassion, and a special kind of acoustics — one where people truly listen to each other.

Janice Kerbel

mentor of the LAB: DOCU/SYNTHESIS x Ukraine War Archive

How do you personally define working with memory in an artistic context?

There are so many different kinds of memory: cultural memory; collective memory; personal memory; unconscious memory; false memory. I think that in order to work with memory productively — in an artistic context — means that you need to straddle all these different, and at time conflicting, forms. In that respect, memory can become active and potent, rather than something relegated to the past.

What approaches to interpreting cultural heritage emerged within the laboratory?

I became very aware of the space that exists between interpretation and reception of cultural heritage. Artists from the laboratory would share their particular understanding of a specific aspect of their own cultural heritage — one which was at times dangerously at risk — and I would try to both understand it and bring my own perspective into the frame. The reality of loss was constant, but so was a feeling of acquisition (of knowledge, or understanding, of perspective).

What was your experience like working in the laboratory format?

The artists were all very generous in sharing their experiences and their practices. It always felt like a privilege, like entering a portal for a brief moment. There was sense of both hospitality and reciprocity, both in the meetings/tutorials and in the artwork shared.

Oleksiy Sai

mentor of the LAB: DOCU/SYNTHESIS x Ukraine War Archive

How do you personally define working with memory in an artistic context?

Unlike information or knowledge, art offers experience. And experience is more important than knowledge. You can forget the rules of how to ride a bike, but not the experience of riding it. That’s why I believe art will leave a deeper memory of the war than the news ever could.

What approaches to interpreting cultural heritage emerged within the laboratory?

Artists working in various media, with different experiences and areas of focus, came together in the Laboratory. I believe the most valuable aspect was that they met in person — which allowed them to exchange experiences and make connections for future projects.

What was your experience like working in the laboratory format?

It was engaging, dynamic, and effortless. During the sessions, we sometimes sparred and exchanged ideas; other times, the artist simply needed to be heard and supported. I found the work productive, and I’m really looking forward to the exhibition to see the results.

Oleksandra Nabieva

curator of the LAB: DOCU/SYNTHESIS x Ukraine War Archive

How do you personally define working with memory in an artistic context?

For me, the most problematic question in this context is: What is a work of art? There are many approaches and definitions. In the context of working with memory, it’s most relevant to speak of self-reflection, affect, and engaging with what remains unspoken in language. Most importantly — a work of art can be seen as a form of phenomenal knowledge, one that deals with experience of such intensity and breadth that it resists verbalization. Overall, I subscribe to the well-known interpretation that a work of art remains a form of striving — or even longing — for truth.

What approaches to interpreting cultural heritage emerged within the laboratory?

I think what’s more valuable here is not to classify these approaches, but to acknowledge that the artists who participated in the Laboratory were able to exercise complete freedom in interpreting cultural heritage. In fact, the exhibition itself — including its spatial design — will serve as an additional layer of reflection on cultural heritage and a commentary on its place in contemporary Ukrainian realities.

What was your experience like working in the laboratory format?

For me, this experience was primarily formative — from the moment I handed over the concept of the laboratory to my colleagues to the stage when the project began to take shape and became a platform for meetings, collaboration, and an intensive shared process.

Roman Bondarchuk

co-founder of the Ukraine War Archive

Why is it important for artists to work with materials from the Ukraine War Archive?

We are constantly looking for new ways in which the materials accumulated in the Archive can work and influence narratives, people's consciousness, and the perception of Russian aggression in Ukraine. Analytical reports, scientific studies, and journalistic publications are often devoid of emotion. And works of art are what appeal to emotions first and foremost. It gives you the opportunity not only to learn about a new story, but also to feel and relive this experience. And this experience remains with the viewer forever, it cannot be replaced or denied.

What are your impressions of the lab format and the finalists’ projects?

I was impressed by the number of applications received for the competition — I didn’t expect to see so many brilliant ideas and such enthusiasm to realize them in inventive forms. I’m glad we were able to create a platform for developing these ideas into fully formed artistic expressions. I’m also pleased that the Archive will be enriched with a collection of artworks that we plan to exhibit on international stages.

The 22nd Docudays UA is held with the financial support of the European Union, the Embassy of Sweden in Ukraine, International Renaissance Foundation. The opinions, conclusions, or recommendations do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union, the governments, or organisations of these countries. Responsibility for the content of the publication lies exclusively with the authors and editors of the publication.