This year, Docudays UA invites you to explore Chilean cinema — an art form that has grown from the ruins of dictatorship and memory. Despite nearly two decades of violence under Augusto Pinochet’s regime, Chilean cinema became a language of resistance and renewal. Director Tetiana Kononenko examines for the festival guide how a new vision of the country emerges in film, through the shadows of what has been forgotten and what cannot be forgotten.

Chilean cinema is the voice of the periphery, where suppressed cultures and forgotten histories sprout on screen. It’s an attempt to reinterpret the past and a question: what survives in the shadows? Themes of collective pain and personal memory unite acclaimed masters with emerging directors who create bold, politically charged films that blur the line between documentary and fiction.

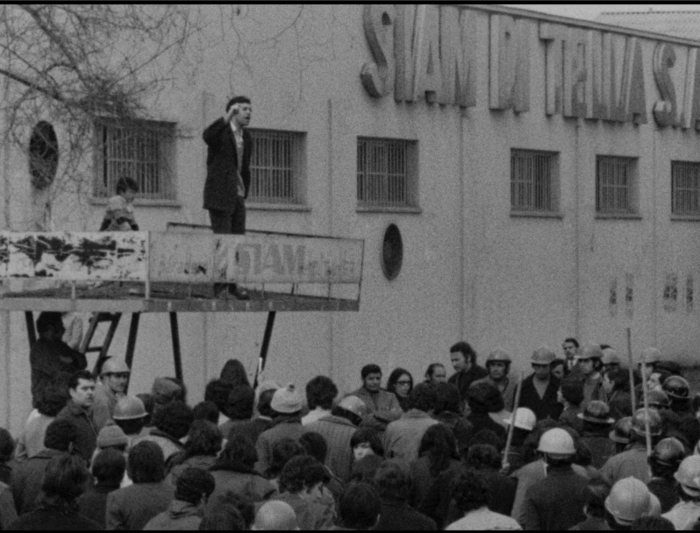

Raúl Ruiz is a foundational figure in Chilean cinema. Socialist Realism was his last film before emigration — a satirical work composed of a series of short stories where two worlds intersect: those of workers and intellectuals. The film became part of the director’s posthumous “trilogy of lost works,” completed by his wife and longtime editor Valeria Sarmiento, herself a pivotal figure in Chilean auteur cinema. Their creative partnership began in the early years of Ruiz’s career and profoundly influenced the visual language of his films. Sarmiento preserved and actively shaped her husband’s legacy, forging her own path in developing women’s auteur cinema in Chile. In Socialist Realism, she doesn’t merely restore old reels — she creates a surreal cinematic space on the border of reality and myth. The film rejects official narratives of memory, portraying it instead as a living terrain of struggle and dreams. This is the path that today’s Chilean films continue to follow.

Still from Socialist Realism

In her film An Oscillating Shadow, director Celeste Rojas Mugica invites viewers into a space of family memory. We find ourselves in a dark room beside the director’s father, a former resistance fighter who, through photography, relives his political and personal history. As a member of the resistance, he fought against repression and human rights violations during Augusto Pinochet’s military dictatorship. In the interplay of light and shadow, a profoundly moving dialogue emerges: one about what has been repressed and left unsaid. Developing photographs becomes an act of remembrance: slow, fragile, and necessary.

Nicolás Molina’s film Pirópolis is much more than a documentary report on the emergency in the hills of Valparaíso. It offers a contemplative, almost dreamlike gaze into the masculine world of firefighters — an institution built on discipline, hierarchy, and traditional notions of masculinity. Women appear as shadowy figures: tolerated, but barely acknowledged. The film refrains from direct criticism of the patriarchal institution; instead, it is embedded in the very fabric of the imagery — in ritualised movements, archaic symbols, and the solemn way heroism is performed. Refusing to be tamed, fire emerges as an element and a fully fledged character — a natural force that relentlessly dismantles human desire for control and order.

In contrast to Pirópolis, Tana Gilbert’s Malqueridas immerses itself in the experience of women’s imprisonment. Instead of order, there is uncertainty. Instead of heroic gestures, there are shadows. The masculine world emerges here as a framework of confinement — bars behind which life resists captivity. The film is composed entirely of footage shot by imprisoned mothers on cell phones inside Chilean prisons. While other films evoke water, forest, or fire, Malqueridas chooses shadows: limited freedom, the echo of memory, a fragile presence. Here, the camera becomes a tool of self-definition, and each image a gesture of resistance against invisibility.

Still from Malqueridas

In When the Clouds Hide the Shadow, director José Luis Torres Leiva discovers a sanctuary for the ineffable in the landscapes of southern Chile, home to the Indigenous Yagan people. Actress María arrives in the world’s southernmost city, Puerto Williams, for a film shoot. But a storm prevents the rest of the crew from reaching the location. During her enforced waiting, María meets locals — including a young Yagan woman who shares the story of her illness and the prospect of her death. This encounter stirs María’s memories of loss and pain. The film contemplates preserving culture as an act of quiet yet unyielding resistance.

Although these films are very different, they are united by a sensibility of memory — one that resides not in grand narratives, but in voices, bodies, and images. Today, Chilean cinema is a reimagining of the past and an attempt to shape the future and give voice to those who have long remained in the shadows.

This program was created in collaboration with FIDOCS — one of the largest film festivals in Chile and Latin America — and developed with the support of the International Renaissance Foundation. Its content does not necessarily reflect the views of the International Renaissance Foundation.

Featured image: Still from An Oscillating Shadow

The 22nd Docudays UA is held with the financial support of the European Union, the Embassy of Sweden in Ukraine, International Renaissance Foundation. The opinions, conclusions, or recommendations do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union, the governments, or organisations of these countries. Responsibility for the content of the publication lies exclusively with the authors and editors of the publication.