This year, our selection of the prominent documentaries which have already graced the screens of the world’s major festivals and become hits includes the winner of the Cannes Critics’ Week Grand Prize, the poetic film Makala by the French director Emmanuel Gras. In Swahili, makala means charcoal. The film, in which few words are spoken, depicts the everyday life of Kabwita, a young villager who lives in a remote region of Congo. On his own, with a small axe in his hand, he has to cut down huge trees which he then turns into charcoal in order to make money for his family. But to sell the charcoal he makes, Kabwita first needs to walk a long distance to the town market. He has to walk on foot for several days in a row along a dusty road, pushing his bike loaded with bags of charcoal. In the end, this story of a person who has to make a tremendous effort to provide for his family in his own country with a bare minimum of goods turns into a poetic tale about strength of will and about believing in yourself to build the future. The film critic Andriy Bondarenko talked with the director Emmanuel Gras about the process of filming, about why people in Congo have to make charcoal themselves, and about how African migrants have reacted to the film.

I really liked your film. It just speaks for itself. But I would like to learn more about the protagonist and his context. How average is the protagonist, to what extent does he represent his country? And how did you find him?

I visited Congo several times even before I started working on my film Makala. I worked as a cinematographer for several documentaries by other directors. In particular, I visited the Katanga province where the events in Makala take place. It is located in Southern Congo, where there is no jungle, where the soil is mostly dry. But there are many mines which work for big industry, mostly foreign companies, and the local population is very poor.

During the filming on the road outside Kolwezi I often noticed people with bikes loaded with charcoal, which they pushed in front of themselves like carts. Kabwita, the protagonist of my film, is one of them, so you can hardly call him unique. Thousands of people from the surrounding villages do it: they bring charcoal to the town and sell it.

In Congo, 90% of all energy consumed by urban residents comes from charcoal. Practically all the food in cities is cooked with this fuel, because there is a lack of electric power. So every day people bring tons of charcoal from villages to cities. I was very impressed by this. I started asking questions: where are they walking from? how much do they make? can they survive on what they earn? I was told that the charcoal is made in the bush (uncultivated territories overgrown with bush and short trees. A. B.). Some producers sell the charcoal to dealers who come on trucks. But many of them transport it to the city on their own in order to get a better price. Most of them are villagers who also produce the charcoal.

So I decided to make a film about this. The idea was very simple: to record the whole process from the beginning, the cutting of the trees, to the end, the sale on the city market. I saw a very direct and very powerful story in it. A certain clear narrative which you can follow to communicate an idea about what life is like in this country. So I met Kabwita and came back a year later to make a film about him.

The film is very simple and at the same time very powerful. How do you achieve it? Do you have some kind of general method, or do you use a different approach every time? I mean, how did you dive into the protagonist’s life?

Makala is my third film. One of my previous films was about the lives of cows, and the other is about life in a homeless shelter. But they were more like general portrayals of certain environments. And Makala became the first film in which I decided to follow a story. In general, my creative method is to capture the feeling of the present moment which is happening right here and right now. To let the audience feel sensually, how it is to cut a tree, to push a loaded bike, to suffer from heat. So I decided to follow Kabwita all the time, in all his actions, so that I could be next to him on the physical level. Also, to give the viewer time to immerse and get a feeling of what is happening, I mostly use long shots. And no voiceover. The central idea is to walk each step together with Kabwita and feel his humanity, his thoughts, without even looking inside his head.

The film is focused on the journey, but for a better understanding of his life I inserted several other moments. For example, when I learned that Kabwita has drawn a construction plan to build a new house, I thought that this should also be in the film, otherwise we would not know why he needs the money he makes off selling charcoal. In any story, it’s important to answer the question: What is the protagonist’s main goal? I tried to make my film as close to a fiction story as possible, so this question was important for me.

What did you personally feel when you encountered the world in which people need to cut down trees in order to survive? Did you ever get the urge to put down the camera and help your protagonist?

Yes, I came from a rich country and I filmed people who live in poverty. So there is a fundamental distance between them and me. But, to be honest, it was more difficult for me to film homeless people in France, because there, I filmed people who barely do anything, they just live in a shelter. And here I dealt with someone who went somewhere, had a goal, had a family which he worked for. Kabwita was constantly busy with something, and he was actually a hero for me, not just a character.

I mean, when I was telling Kabwita’s story, I did it primarily to honour him, to show how heroic he is in his life.

As for the desire to drop the camera and help, it’s an interesting question. It’s more about some kind of ethics. Of course, I wanted to film all the difficulties which Kabwita faces during his trip. So I had an agreement with him: if Kabwita needed any help, he was supposed to tell us, and we would stop the filming and help him. So he was responsible for the whole process. As long as he didn’t say anything, we just filmed. There were three of us in the team, and we were constantly near. Sometimes serious critical situations happened, when we had to intervene. These moments are not included in the film. For example, when Kabwita pushed the bike uphill to the railway causeway, we had to help him to cross the rails. But we did it only in extreme cases. So the whole film is filmed on the edge of critical situations.

Of course, it was very hard to just stand aside someone who is doing something difficult. But that was my job, to show this process. In addition, we also walked that road with Kabwita, we did not watch from the distance, we were also there, in the dust, amidst cars.

As far as I remember, the whole journey took two days of walking.

Actually, the whole journey took five days. If Kabwita walked alone, he would have made it in two days, but we had to stop quite often for technical reasons. Although in the film, we showed how the uninterrupted process would look like.

At first, I thought your film was an epic poem of hard labour, like The Naked Island by Kaneto Shindo. But in the end the protagonist’s image seemed to me like a more universal metaphor of the general human condition in the contemporary world, when society is increasingly turning into a mechanical combination of individuals where everyone is by themselves. The film seems to ask the question, “How much can one person do without help?” And the answer is, “Not so much.”

What you said in the beginning, about labour, that was actually my idea – to show the situation of people in countries like Congo. There, you must work hard and suffer just to survive. Society doesn’t care about you at all, if you don’t do anything yourself, you will die – there are no other options. I wanted to show this picture, reduced to the basic essence. Either you do all that, or you’re finished.

I don’t know how universal it looks, but it does have a certain metaphor in it, of course, a metaphor of our general human situation, if we develop the idea to the maximum. However, Kabwita’s loneliness in the film was not essential. In fact, many people produce and sell coal in groups. I focused on Kabwita not because of any ideological thinking, but only because it is easier to show the whole process by using the example of this one person, how hard it actually is, how much effort it requires and how little it is worth in its monetary equivalent. This contrast between the effort invested and the economic value was very dramatic for me. I actually filmed Kabwita, who does everything alone, precisely to highlight this dramatic note. Meanwhile, in groups everything looks more complex and less clear.

On the one hand, Kabwita’s life looks like total suffering. On the other hand, he has his own place in life, he has a job, a family and a faith. How do you see his internal evaluation of his life?

It is always hard to judge about other people’s perspectives. But I tried to show as best I could that Kabwita has his own life. He knows that his life is not easy, he knows that his country is rich in resources, but only the foreign industry and the corrupt politicians profit. He is a smart man and he understands very well what is happening around him. But this is his full life, he doesn’t want to go anywhere. He wants to survive, and also to move forward: to build a proper house with a garden, with a pond and ducks, he wants to educate his child. Kabwita sees the future and wants to develop. He is not an optimist, but he also doesn’t despair: he is just aware of the situation and knows that he faces hard labour, he knows how to deal with it.

In the last scene of the film, we see Kabwita praying. But I think he understands that in the end, everything depends on him. He does not expect help from God. It is just important for him to express himself, to express his feelings.

Distress and suffering is the usual stereotypical image of African countries. To what extent does this image correspond to reality?

It is hard for me to speak about Africa in general. Different countries there have different situations. Even Congo is a big country, of which I’ve seen only a part. But what I can say about Congo for sure is that it is indeed one of the poorest countries in Africa. What I’ve seen there does indeed correspond to the stereotypical images. In its own way, it’s all true. It is a country of poverty, suffering and exploitation. Its natural resources go outside the country, and they are destroying their land to survive: there’s no electricity, no fuel. I mean, Congo produces enough energy, but the establishment knows that it is impossible to sell to the population and make a profit, so everything goes to South Africa. And the locals have to cut down trees to cook food for themselves. It’s a horrible situation. The country has big industry and capital, but they have nothing to do with the population. The establishment are just predators who behave as if they don’t owe anything to the society and just make profits. Congo is a country of poverty for the majority and wealth for a handful of people.

Are you concerned about how the audience perceives your film? That is, whether they understand your idea correctly?

There are always problems with that. A film is not an analytical book where you consistently explain what you wanted to say. Here, the conclusions are more open, you just show something. I don’t make films with a very clear message. My idea is to help the audience experience something, to put them in another person’s shoes. You just stay near them and at the same time you learn something about their life.

African migrants often ask about the film Makala if I want to show why all of them want to go to Europe so much. I understand why they have these questions, but I really don’t like it. Because I’m showing someone who wants to live in his own country and has a goal which he is pursuing at home. He just wants to live better in the place where he lives. And when the audience perceives him through the prism of migration, that is terrible for me, because the film is not about that at all.

But I can’t do anything about it. I understand that when the message is not very clear, you need to accept that different people see different things in it, things you did not intend to put into it.

Interview by Andriy Bondarenko

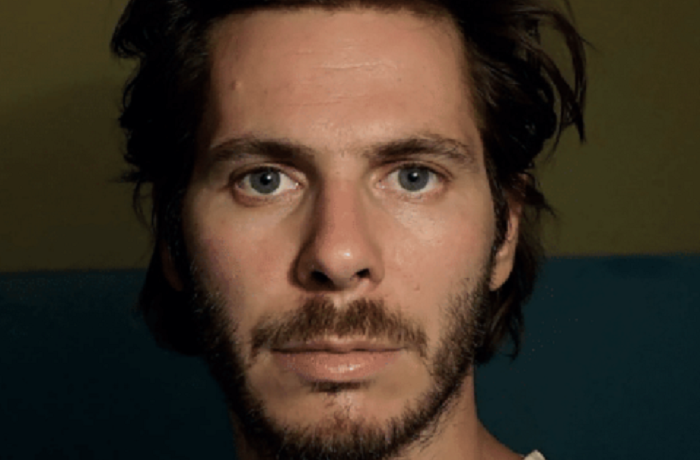

Header photo: Emmanuel Gras